Click on a book to read its review.

Click on a book to read its review.

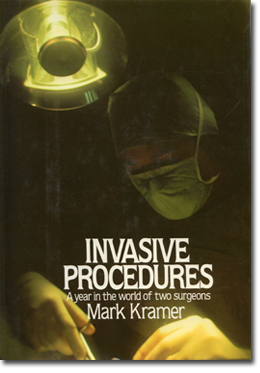

INVASIVE PROCEDURES: A YEAR IN THE WORLD OF TWO SURGENTS

By Mark Kramer

Harper and Rowe, 1983. 213 pp.

Review by: William Patrick

EXAMINING THE LIVES OF SURGEONS

Sunday Boston Globe Book Review

8/28/1983

Edition: N, Section: BOOKS

It begins shortly after dawn in a hospital near Boston. The surgeons are

scrubbing, the patient is slowly losing consciousness and the reader,

confronted with nothing more threatening than the names of the instruments, finds his palms beginning to sweat. But "Invasive Procedures" is not a medical thriller. It is superb reporting - humane, witty and frighteningly perceptive - a portion of which appeared recently as an Atlantic Monthly cover story.

Since the days of "Young Doctor Galahad," America's fascination with

doctors has progressed hand in hand with the rise of a medical aristocracy,

nurtured by a medical-industrial complex. At the top of the peerage are surgeons, who owe their rank and privilege to the fact that, when something ails you, they can simply go in and fix it. They are the consummate technicians in a society enamored of gadgets.

Intrigued by this grisly profession, writer Mark Kramer spent a year with

two Massachusetts surgeons, attempting to probe their lives as they probe

the bodies of their sleeping patients. He leaned over their shoulders

during dozens of operations. He sat in on office visits. In scrub rooms,

recovery rooms, corridors and cafeterias, he interviewed not only the

surgeons but nurses, patients, referring internists, anesthesiologists -

virtually everyone who comes into professional contact with these men. He

also stayed at their homes and talked with their kids at breakfast. He

traveled to the surgeons' own childhood homes to hear parental

reminiscences. Seemingly, like the in- flight recorder up front with the

pilots, he missed nothing. He witnessed moments of cool precision in the

midst of crisis that show why society rewards these men with $200,000 a

year. He also witnessed behavior so puerile that, if exhibited by a

15-year-old, it would call into question the teen's readiness for a

driver's license.

"Doctors are little boys," a nurse confides after one particularly childish

episode. "We treat them like that." At another point, one of the surgeons,

relaxing on his lawn, admits, "I don't do much introspection. In fact, I

avoid it. I avoid it as a function of the human creature. I wouldn't step

out the door in the middle of winter without dressing up warmly. It's cold

out there . . ." So Kramer's surgeons insulate themselves, with tough

psychological hides, with nurses, secretaries, tax shelters and with strong

political lobbies.

But arrogance, clubishness, and bravado is the standard profile of the

"surgeon's personality." What is new and extraordinary in Kramer's account

is the acumen with which he makes us understand the cycle of pressures,

demands and gratifications that underlie the stereotype. (Seeing the surgeon in surgery, Kramer says, is like hearing a man with a Hungarian accent begin to speak Hungarian.) Time after time they must tell the patient that it's cancer. They must amputate the leg, remove the breast, watch the young accident victim die. They have a depressing psychological burden, coupled with an exhilarating power. In one macabre scene, one of Kramer's surgeons slashes open an unanaesthetized patient to restore a failing pacemaker. As the doctor jiggles the wires, the patient pops in and out of life like a puppet, talking one moment, lifeless the next, brought back, lost, brought back from death again.

Like his subjects, Kramer is a master of his craft. Occasionally, he will

slip in a quote from medical sociologist Renee Fox; once or twice he offers

statistics from the New England Journal of Medicine. But what he shares

with the reader is the raw experience, not the research. We're swept along

by action, character development, and the telling phrase, while Kramer's

pattern and purpose lie unobtrusively beneath the surface. There is

tension, drama, as well as the obligatory dark humor - the plumber whose

intestine was accidentally sewn shut, the nurse who moonlights as an

embalmer. In fact, squeamish readers may find more vicarious experience

than they have bargained for. The smells and sights and sounds of

amputations and ruptured aortas are rendered vividly and are not pleasant.

In the end, Kramer offers a point of view which surgeons themselves know

little of - ambivalence. He admires and even envies their skill and their

usefulness and the gratification that it brings them, but he also finds

them sadly isolated from the real world, retreating to the operating room

because that alone is where they feel comfortable, indispensable and

totally in command. If there is a message in these observations, it is the

reminder that surgeons have a limited view of the human condition. True,

inside the operating room we want no poet's tears dropping into the

incision. But before the cutting begins, and especially when deciding

whether or not cutting is the answer, physician insensitivity can be

dangerous. We buy a surgeon's skill and judgment just as we buy any other

service. Let the buyer beware.